We No Longer Dare to Dream

How to reignite our optimism for the future

Grandeur and ambition once danced within our visions of the future. There used to be a vibrant allure; cities gleaming with the sheen of technological prowess, cars taking flight through the skies, and robots attending to mundane tasks. These felt not like figments of imagination. They felt like glimpses into a future waiting to unfold.

But that was at the heart of the twentieth century. In 2024, this unyielding optimism for the future feels… faint.

Instead, we are inundated with prophecies of humanity's downfall; economic despair, Orwellian state control, global warming, population collapse, forever wars... you get the jist. It seems implausible that tomorrow will not be terrible, let alone better.

This perceived erosion makes the future a tough sell. Discussions of new frontiers in science, technology and social progress now bring fear and resentment. There may even be an eye roll of derision at the audacity to ponder ‘progress’ amidst the present doom.

I suppose this reasoning has some merit. If our ancestors were blindly optimistic, we would not be here today. Without the right dose of fear and caution, they would have fallen victim to predators or environmental hazards (or stupidity). But we now have social media. We now process every problem, every crisis, every opinion.

With enough doom hanging over us, pessimism becomes our constant companion. So much so, that we have converged - we think, speak and see like pessimism. This is why we have lowered our expectations for the future, it’s what pessimism would do.

But I think this perspective is short-sighted.

Firstly, there is the issue of perspective - the reality you observe on your social media feed is only a snapshot, it lacks context and detail. It may even be fabricated content.

This doom perspective also neglects to consider humanity’s ingenuity up to this point. After all, you are reading this from your phone, tablet or laptop; this means you have access to abundant energy. You have the time to read a random blog on substack; this likely means you have sorted food, water and shelter. The threat of a barbarian horde at your gate is probably also unlikely.

If you are fortunate to have answered yes to these assumptions then enough people in the past did something right. Whether they intended to or not, whether you knew them or not, they built a better world. No means perfect, but better.

So why are we so 'doom and gloom' about the future?

I think a quick history lesson can shed some light.

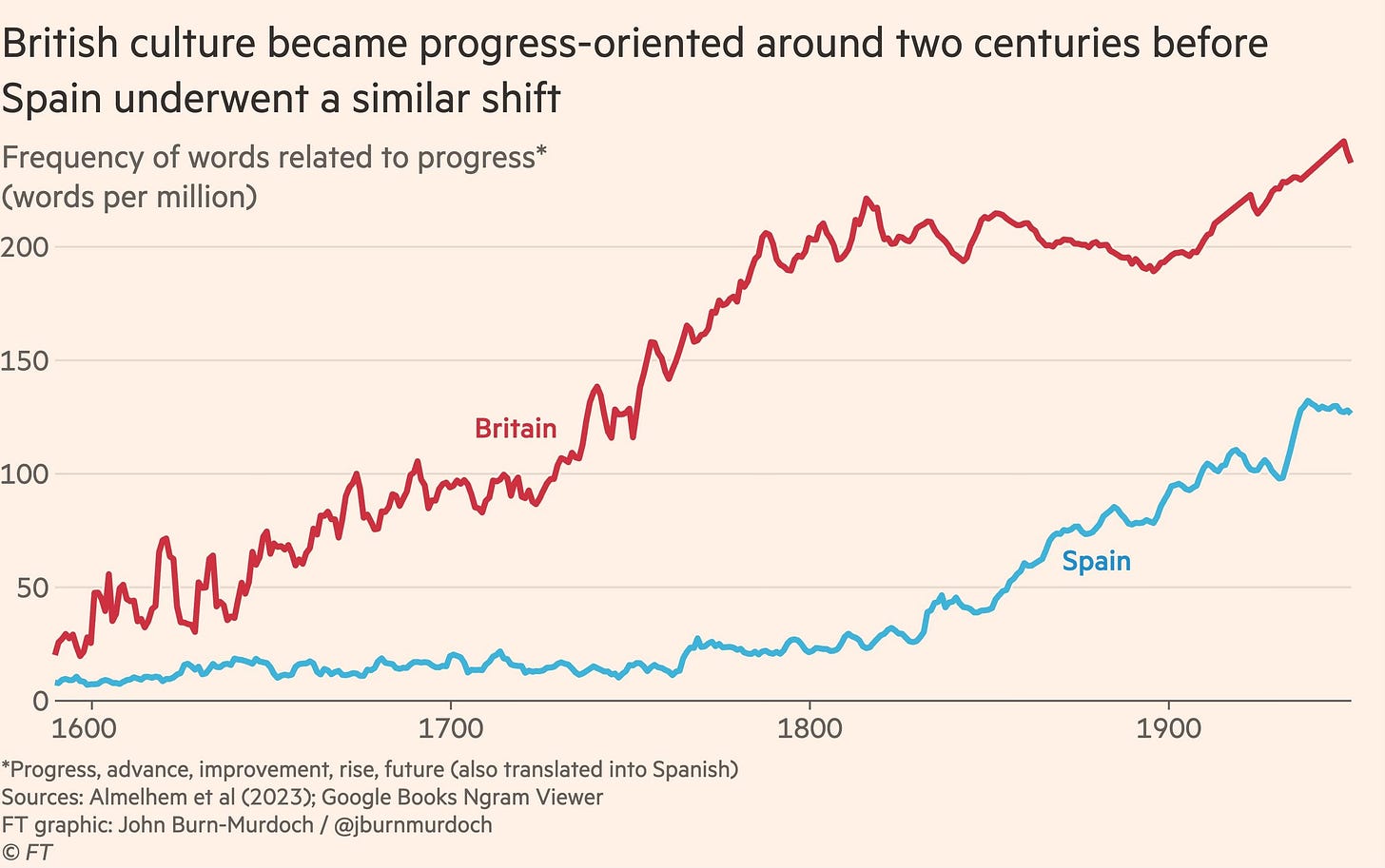

A study conducted by Almelhem et al. (2023) explored the connection between enlightenment ideals and societal advancement. The researchers analysed over 173,000 books printed in England between the 16th and 19th centuries, to track how often certain terms were used in this period. They used this as a proxy for the cultural themes of the time. Their findings indicate that leading up to the 18th-century Industrial Revolution, there was an uptick in terms related to progress, science and innovation. British society was evermore engrained with enlightenment ideals.

Furthermore, an article (X.com link also) by John Burn-Murdoch tracked the frequency of terms in Spain across this same period. He suggests that Britain and Spain were in a similar state of prosperity at the beginning of the 17th century. But Britain, with its greater orientation toward science and innovation, developed the conditions to experience far greater levels of prosperity later on.

The lesson here is that if we think and speak of enlightenment and optimism enough, we steer ourselves toward optimistic futures. The counter must also be true. If we think and speak of doom for long enough, doom becomes prophecy.

After all, countries like Britain, the former bastion of the Industrial Revolution, are experiencing economic stagnation today. I think, in part, this is a reflection of the established and ever-growing pessimism in the cultural psyche.

Our chosen mindset shapes the behaviours that will determine our fate.

What has shaped our current theme of doom and gloom and where can we intervene?

Hint: Perverse Incentives.

Perverse incentives are systems that encourage us to engage in behaviour that is counterproductive to the intended goals or interests of that system.

Here are some examples:

Safetyism

This is the tendency to prioritise the minimisation of risks and potential harm. On the surface, this seems sensible. But extreme or simply prolonged safetyism leads to hyper-vigilance. It aims to guard against any conceivable harm. This ethos of 'safety at all costs' may result in the erosion of civil liberties, free expression, and intellectual diversity. Unconventional ideas are now a threat.

Challenging or disrupting the status quo is necessary for progress and innovation. Novelty can present risk but overwhelming caution means the leap is not taken.

Formal Education System

The intended goal: To facilitate the distribution of knowledge, skills, and values to individuals within a society. This prepares them for personal and professional development.

What has happened: We are taught what to think, not how to think.

Standardised testing is the typical measure of student and school performance. This leads to teaching strategies that prioritise test preparation. Therefore, memorisation of facts and regurgitation of them is highly valued in the education system. Unfortunately, this is valued higher than fostering creativity, critical thinking, and reasoning ability.

This narrows the curriculum to topics that are most compatible with standardisation. Areas such as philosophy, arts and practical ‘life skills’ are neglected. This inhibits the ability to think creatively and holistically about the world. Instead, it creates a system of thinking in conformity, the antithesis of innovation. Conformity also raises the perceived social price of being wrong. Playing it safe means sticking to the playbook of memorisation and regurgitation. This becomes the favoured way to learn.

This system fools many of us into associating ‘learning’ solely with ‘school’. Without the formal requirement, how many of us choose to read a book or bother to learn a new skill? Thinking back to school, for many of us, it was the bell ring that brought satisfaction. It signalled a lunch break, the end of the school day or the end of the school year. That is not a system that creates dreamers, inventors and collaborators.

Cultural Norms - Tall Poppy Syndrome

We can easily blame politicians and bankers for our woes of cultural and economic stagnation. But the people are not without some responsibility.

Tall Poppy Syndrome is characterised by the criticising or subtle ‘cutting down’ of those who are seen as too successful or simply ambitious. As the name implies, non-conformists must be taken down a peg. In the UK for example, where I am writing from, ‘tall poppy syndrome’ is common. Perhaps, originating from historical British values of modesty, humility, and egalitarianism. Values that are still present today. These are admirable values, but, like anything in life, we need to strike a balance.

This syndrome can discourage an aspiration for greatness. Simply dreaming big feels ‘silly’.

We can observe the polar opposite of this in American culture, hence 'Silicon Valley' and widespread entrepreneurship. But, on this opposing side of the spectrum, there can be too much dream-enabling. This can lead to fragility when reality inevitability throws a curveball or two. But that’s a blog post for another time.

Worse still, other forces exacerbate tall poppy syndrome. Take economic inequality for example. Those who perceive themselves to be watching from the bottom may develop a distaste for wealth and those who possess it. Therefore, attributes of the wealthy become unfavourable in the public eye. Some of this is well deserved with instances of greed and corruption. But painting everyone with the same brush ignores the value provided by those who truly innovate and change the world in positive ways. Hence, the compensation they may receive for their contributions.

The point is, that our lack of ambition and innovation can also be self-inflicted.

Hedonic adaptation

This is the human tendency to acclimate to new circumstances, leading to a diminished sense of appreciation over time. As innovations become commonplace in society, their novelty fades, and we take them for granted.

This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in affluent societies, such as the so-called 'West'. Pre-industrial hardships have been largely eradicated here and a cultural amnesia has developed. We are no longer involved in many of the processes that keep society functional due to our ‘laptop economy’. This has shielded us from seeing how far we have come. Because of this, we also undervalue the effort and ingenuity needed for even the smallest steps of technological and industrial progress. This can create a false sense of expectation that innovations will always occur. But if everyone expects, who is imagining, designing and creating?

Overstimulation

Our mind needs free space to accommodate the bandwidth required for imagination and creation. TV, video games, social media and YouTube provide a steady and constant drip of stimuli that hijack this bandwidth. This depletes our compulsion to go through the creative thought process because we are never bored enough to trigger it. Essentially, the itch is always scratched.

A healthy dose of boredom can serve as a form of productive discomfort. It drives us to push beyond our comfort zones to explore uncharted territory in pursuit of creative expression. And solve a problem or two along the way.

‘As you sow, so shall you reap’

An optimistic future must be built. But to do so, we must want to build it. This is only possible if we value the future enough, beyond even our lifetime. Notice a common thread between the perverse incentives discussed - they are characteristic of short-term priority.

This short-termism is shaped by the pressures of immediate results. Evolutionarily, there was immediate pressure to survive day to day. Economically, if an organisation does not focus on the near-term profit, it may not exist long enough to carry out long-term visions. Politically, public servants and policymakers are measured against a couple of years, not a couple of decades. In education, we measure teachers and institutions by test scores and graduation rates. Not by how many winners they develop for Nobel and Pulitzer prizes.

"A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit"

Valuing the longer term does not come easy to us. We are mortal beings with lifespans that are short, relative to the cosmic scale. We want to experience the fruits of our labour, not merely plant the seeds for future generations to enjoy. Especially as they are strangers to us. Especially as the short-term requires our full attention.

I agree with the doomers that we face challenges that could put us on an undesirable trajectory. But I write this due to my frustratration with the usual prescriptions of 'do nothing', 'complain' or 'wait until the government fix it'. The challenges we face are the consequences of people in the past choosing the short-term fixes. They kicked the can down the road.

Not prioritising meaningful creation and the outcome of living in a stagnating society are not exclusive. It is because of this complacency that we are experiencing these shortcomings. As Charlie Munger stated - "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome".

A dose of long-termism enables us to break this vicious cycle. It’s the realisation that it’s not about sacrificing for the future; it’s about investing in it. This is a value system update. One which prioritises long-term benefits over short-term gratifications. With this value system, we are more likely to set better incentives - financial systems that do not devalue currency; governance structures that encourage healthy corporate competition; and educational systems that create the pioneers of tomorrow. I could go on.

It is about recognising our interconnectedness with the people of the past and future. What if someone in the past had initiated a global nuclear war? The world today would undoubtedly be different.

If you find the ‘interconnectedness’ argument to be trite, then consider the power of momentum. It took 200 years of persistent promotion of Enlightenment ideals before it finally integrated into 18th-century Britain. Only then could the Industrial Revolution be forged. This means that any disruption to cultural momentum is significant. It determines if the window of opportunity to improve our fate exists, and for how long it is open.

Shaking free from this trance of self-loathing and prophetic doom is critical. For some, it has become a comfort, a relief even. Freedom from having to take action. Freedom from responsibility. This is because they can reassure themselves - “what’s the point if doom is coming anyway?” But the research by Almelhem et al. (2023) serves as a rationale — a reminder that progress is not an inevitability, but a choice.

Reflect on civilisation so far. Pick any point on this timeline and you are reminded of the resilience and ingenuity that have driven us forward. Even in the darkest times, darker than ours. The conveniences of modern life are a testament to the efforts of those who came before us. Whether by design or accident, they passed the baton forward.

Yes, there seems to be a new war every year. Environmental degradation could lead us to an apocalypse. Inflation is making us all poorer by the day. But the window has not yet closed.

The cultural revolution that we need does not have to be ‘French’, we need not burn everything down (yet). What the visions of flying cars and gleaming cities of the 1950s and 60s failed to highlight is the philosophy required to achieve it. A 'Tomorrowland' is not just a destination or technological fix - It is a state of mind. It is the audacity to dream.

Let’s stop kicking the can down the road.